For those with long memories, the years 1973 and 1974 were difficult times, economically, in the United States. An OPEC oil embargo caused gasoline shortages in the United States.

In addition, a recession was in full swing as Americans tightened their belts, hunkered down and spent money on necessities and little else.

As a result, times were tough at the fledgling Walt Disney World, which opened in 1971.

“We were down 800,000 in attendance and the reason was the gas crisis,” Marty Sklar, the former creative leader of Walt Disney Imagineering, recalled in a 2015 interview. “Everybody got scared. Gas escalated from 38 cents a gallon to 54 cents a gallon. Everybody panicked across the country. There were lines and rationing and all of that.”

In May of 1974, less than three years after the Magic Kingdom theme park at Walt Disney World had opened to a resoundingly positive response, then-Disney president Card Walker announced plans for the second phase of the Florida Project.

He took the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, or Epcot, off the back burner, where it had resided since Walt’s death in 1966, and made it the company’s top priority.

“That was really the start [of Epcot],” Sklar said. “I give Card a lot of credit, because he didn’t let Walt’s dream die.”

Walt’s vision is very much alive today

Sklar felt that the dream — a city of tomorrow — could never have been achieved as Walt first envisioned, but that it is very much alive today at Epcot and throughout the Walt Disney World property, even though an actual metropolis never made it past the planning stages.

“Right now, if you go to Walt Disney World on a peak day, there are 300,000 people on that property,” he said, “so you’ve got a community, you’ve got all the functions of a community. Transportation, housing, food, you’ve got to handle everything.”

When Walker decided to push ahead with Epcot, he and his team quickly realized that building a city of the future was a visionary idea that only someone like Walt Disney could produce.

“From the outset of planning and through the design, construction and installation stages of Walt Disney World, Epcot has been the ultimate goal.”

That goal, however, would be much different from the vision Walt Disney had sketched on a napkin and talked about with such conviction during the early stages of the development of The Florida Project.

In 1974, mockups for the “new” Epcot called for a showcase of nations, sort of a permanent world’s fair. But even that idea, as Walt said in the Florida Film, would change “time and time again as we move forward.”

Preliminary plans for this “new” Epcot called for a variety of nations hosting pavilions to showcase their cultures, lifestyles, and wares. But even that simple idea met with resistance.

That rule virtually eliminated countries from participating.

“If you notice, you don’t see any flags flying in front of countries in the World Showcase,” Sklar said. “There’s no nation representation.”

Except for Morocco. “When the king speaks, that changes everything — so Morocco is there as a country,” Marty said. “The king decided he wanted to be in, but he’s probably not a member of the BIE.”

To get around the BIE’s rules, Disney executives went to major corporations within a variety of countries to get them to pony up money. “That’s why you see all those corporate sponsorships in each of those pavilions,” Sklar said.

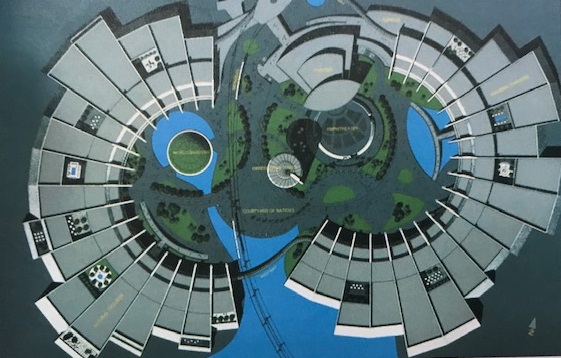

Early renderings showed a courtyard of nations

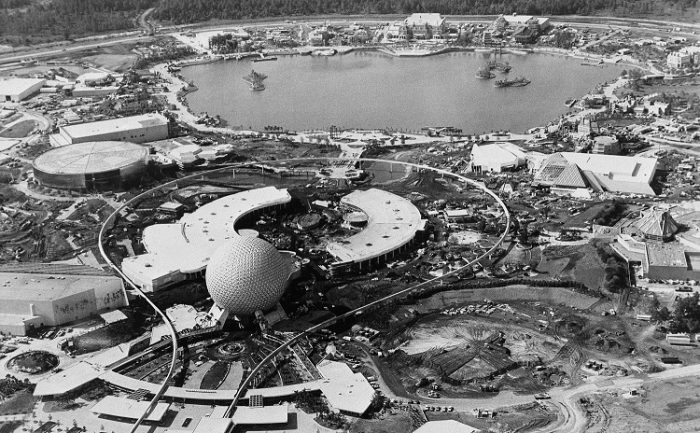

Early renderings of Epcot showed a design concept with two semi-circular structures surrounding a massive “courtyard of nations.” In the middle of the courtyard was to be a giant observation tower, with monorail beams located nearby shuttling guests to and from the Magic Kingdom.

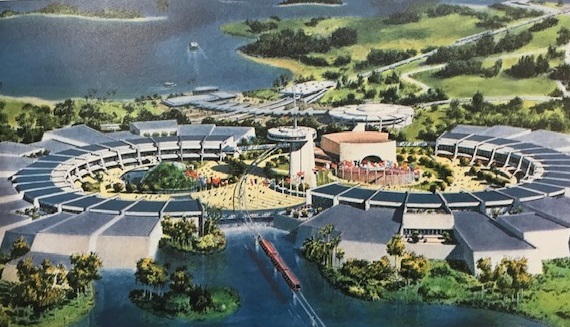

As plans evolved, a second proposal was added to the mix, one which borrowed from Walt Disney’s idea of creating an environment where “we will always be introducing, and testing, and demonstrating new materials and new systems.”

American industry would take center stage here, giving guests a glimpse at what the future might hold, technology-wise, with a variety of high-tech exhibits, many of them hands-on.

When push came to shove — literally — Marty Sklar and fellow Imagineering executive John Hench took the models of the two venues, slid them together, and the Epcot we know today was born.

Once that dilemma was solved, a bigger question arose for Sklar: “How do we pay for all this?” As Walt Disney said when he bankrupted himself in creating Disneyland, “These ideas cost a lot of money.”

“Some aspects, some version [of Walt’s Epcot concept] would have happened and it would have changed a lot, because the evolution of these projects is so dynamic,” Sklar said.

Discovering what Epcot’s mission would be

So Sklar and Hench, as well as fellow Disney executives Carl Borgirno, Don Edgren and Randy Bright, embarked on a veritable crusade to discover exactly what Epcot’s mission should be … and how that vision would be paid for.

What Epcot wouldn’t be was just another theme park. “If you think about it, at that time, and even today, it had to have that contrast,” Sklar said.

“Why should we go into competition with ourselves? So the contrast was good. The big thing was that we decided we had to test the water, so we held what we called The Epcot Future Technology Forums, starting in 1976.

“Ray Bradbury [the noted science fiction writer who would become a key contributor to Epcot’s planning] was the first speaker. And we invited people from academia, from government, from corporations and just smart people that we found through our research and it was really fascinating because we had these long discussions.

“Well that was very nice to hear people say that, but what the heck do you do about that? I went back to Card Walker, who was a marketing man from his experiences with the studio, and we decided to go back to the whole idea that Walt had said, that no one company can do this by itself.

“And that’s when we started going out to all the big corporations and said, ‘OK, here’s what we’re planning to do and we want you to be part it.’”

‘A huge selling job’

Getting American industry to fall in line “was a huge selling job,” Sklar remembered. “There were a couple of key moments in it. For one, we found a man who came to one of our conferences. His name was Tibor Nagy. And he was one of the chief scientists at General Motors and he’d come to this conference intrigued. ‘What the heck is a Mickey Mouse organization doing in this other field?’ he said.

“And he got intrigued with the project and he was on a committee at General Motors called The Scenario 2000 Advisory Committee. Tibor called me and said, ‘I’m gonna go to [GM chairman] Roger Smith and suggest that you get invited back here to make a presentation about this project.

“We packed up two truckloads of models and artwork and we hired John McClure Sr. John had been the art director for the Hall of Presidents, but more importantly, he was one of the great art directors in Hollywood. He did Hello, Dolly and Cleopatra, among other things, so John set up our presentation.

“They gave us the whole design center in Warren, Michigan. They had an area where they introduced their cars. It was big … huge. They gave us the whole thing.

“We made a big presentation to Roger Smith and his Scenario 2000 Advisory Committee, and when we were finished, Roger said ‘I want to do this. There’s only one problem: I’ve got to convince my management.’”

Smith was GM’s vice president of finance at the time, later chairman.

“Jack Lindquist and I were left behind and the next day at 7 o’clock in the morning, we made a presentation to Pete Estes, the president of GM, and they became the first ones to sign a contract at the end of 1978.”

From that point on, American industry seemed eager to follow General Motors’ lead and quickly signed on to be part of this exciting Epcot project.

Next time: With corporate backing, Epcot begins to take shape.

Join the AllEars.net Newsletter to stay on top of ALL the breaking Disney News! You'll also get access to AllEars tips, reviews, trivia, and MORE! Click here to Subscribe!

Trending Now

You need to check out these new Stanley Cup colors on Amazon!

Let's have a chat about an Oura Ring that Disney Adults just can’t seem to...

Get over to BoxLunch NOW!

It all starts on July 8th!

This MagicBand+ hack can make a world of difference during your next Disney World trip!

The resort's refurbishment lineup continues to grow.

If you are flying home from Disney World with these souvenirs, be extra kind to...

Have you seen Disney Visa's newest Disneyland 70th card design?

Going to Disney World alone isn't as scary as you'd think...

Let's take a look at Disney World restaurant menu changes that happened this week.

Here are the park bag mistakes you might make when going to Disney World and...

Making park pass reservations as an Annual Passholder is changing BIG TIME this month!

If you're an introvert, should you head to GEO-82 or find another lounge in Disney...

Grab these discounted Disney gifts online RIGHT NOW!

There has been a BIG change in Magic Kingdom!

There are TWO new MagicBand+ online right now -- grab them while you can!

This Disney Springs restaurant is MAJORLY underrated in my opinion, and I won't stand for...

We tried a new Oreo Tiramisu that we're obsessed with in Disney World!

There are plenty of airports to choose from when flying to Disneyland!

Here are a couple of clues about Mickey's Very Merry Christmas Party 2025 at Disney...