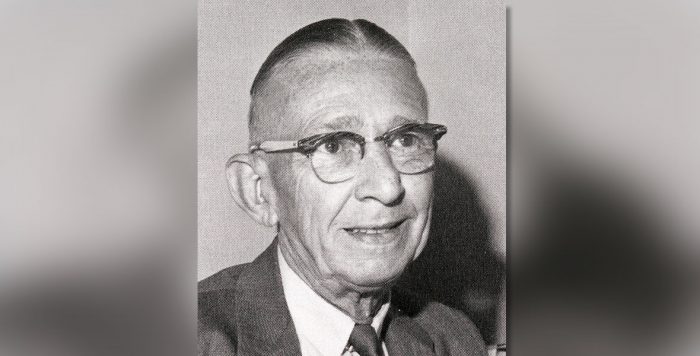

He was short in stature, but a big man when it came to getting the word out on The Happiest Place on Earth.

Eddie Meck was already a Hollywood legend when Walt Disney hired him in early 1955 to promote Disneyland, his bold foray into the uncharted world of theme park entertainment. It was, on the surface, an interesting hire by Disney, considering that Meck had made a name for himself in the motion picture industry as what was known as a “planter.”

Meck was born and raised in Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. In 1919, at the tender age of 20, he began working for the Pathe Company in Chicago on its night inspection crew. Just two years later, he took a job in promotion as a member of Pathe’s publicity staff in California.

His job description included promoting everything from Harold Lloyd comedies to the Perils of Pauline serials, all silent films.

He joined Columbia Pictures in the early 1930s, where his career blossomed as the movie industry transitioned to “talkies.” He helped promote several classic Frank Capra comedies, including It Happened One Night and Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

Later in his PR career, Meck was a planter for RKO Studios, which at that time distributed Disney films.

“Eddie was an old-line movie publicist who knew everyone in the newspaper business, it seemed,” former Walt Disney Imagineering leader Marty Sklar said several years ago.

To give you an idea of how well-respected Meck was, Sklar added: “I was with him once in the late 1950s, when Norman Chandler, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, stepped out of a board meeting to greet Eddie, and ask about Gertrude, his wife.”

Sklar was hired to work full-time in Disneyland’s publicity department in 1956 after graduating from UCLA. He made a lasting impression the year before, after being hired by Walt to produce The Disneyland News, a four-page broadsheet newspaper that was sold to park guests during the months that followed the July 17, 1955, opening.

After earning his degree, “Eddie was my immediate boss at Disneyland,” Marty said, and together with future Disneyland president Jack Lindquist and Disney Legend-in-waiting Milt Albright, they went about the task of educating the public about the grand experiment known as Disneyland.

Over the years, they dreamed up things like Grad Nites, Disney Dollars, Vacationland Magazine and the Disneyland Ambassador Program.

Meck took a rather unique approach to the task of promoting Disneyland: “Two months after the park opened, I told Walt that I didn’t see how he could plant stories [in the press] about Disneyland,” Meck said. “It’s too fantastic and too hard to describe. So, I told him we should bring the press here and let the park sell itself.”

Meck’s strategy was to admit members of the press — as well as their families — into Disneyland, where they could explore and see everything for themselves. It was a plan that reaped benefits for decades to come.

“If you have a good product,” he said, “it’s easy to get the message across. No gimmicks. Just truth and honesty. The greatest product is right here. Walt Disney.”

According to veteran news columnist Joan Winchell, Eddie was “a complete enigma to us [newspaper reporters]. How the heck can you light up like a Christmas tree 365 days and nights of the year raving about the very same thing? But Eddie does, claiming that every day [with Disney] is different.”

Marty Sklar worked under Meck in Disneyland publicity until 1963, when he was transferred to WED Enterprises, the forerunner of Walt Disney Imagineering.

“When I started working on the New York World’s Fair shows in 1961, I kept my role in publicity at Disneyland,” Sklar said. “But by 1963, that was too much for me to handle – and the World’s Fair shows demanded more attention. So, I was transferred ‘officially’ to the WED staff in Glendale in 1963.”

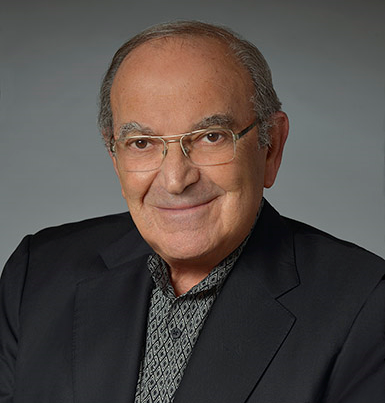

After working in radio and newspapers as a reporter in Pennsylvania and Illinois, Ridgway and his bride Gretta moved to southern California, where he landed jobs with several papers, including the Los Angeles Mirror-News and the Long Beach Press-Telegram.

Among the beats he covered? Disneyland. He produced a two-page, pre-opening day feature on the park and, in fact, was on hand for Disneyland’s opening day. And he continued to write human-interest stories on Disneyland in the years that followed.

When Sklar was transferred out of Disneyland PR in 1963, Ridgway was on the short list to replace him.

“With Charlie’s Los Angeles-area newspaper background, we all knew him before he joined the Disneyland publicity staff,” Sklar said. After Sklar’s departure, “that was when Charlie was hired, replacing me at Disneyland.” Meaning Ridgway was now working for Eddie Meck.

According to Ridgway, Meck “knew how to make friends of news people by visiting with them, getting to know their likes and dislikes and those of their children and grandchildren. He made annual trips — always by train, because of his fear of flying — to New York, Cleveland, Washington and Chicago. He spent hours on the phone and in person talking to editors and writers all over southern California, which was our prime market.”

“Eddie needed a writer like me because he couldn’t write a press release to save his life,” Ridgway said, “but he had more good friends among newspaper and magazine reporters and editors than anyone I ever knew.”

Ridgway was a disciple of the Meck PR style, adopting many of his same philosophies and enhancing what would become known as the “press event.”

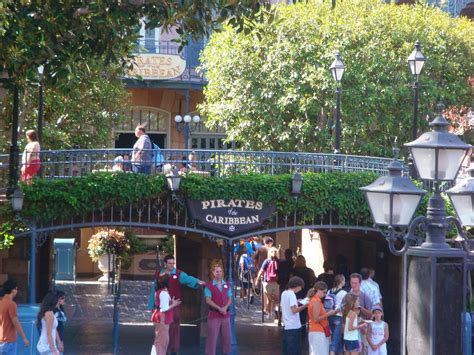

Perhaps Ridgway’s most ambitious press gathering came when the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction opened in New Orleans Square in Disneyland.

“I think it was July of 1966 when we opened New Orleans Square,” Charlie remembered. “Pirates of the Caribbean was to be the principal attraction there, along with restaurants, staging areas for musicians and a merchandise shop or two. Club 33 was upstairs, which was originally intended to be Walt’s apartment.

“The problem was that the Pirates of the Caribbean ride wasn’t ready. They ran into a problem with the boat going down the slide and when it hit bottom, the splashed water into the boat would have drowned everyone present.”

When New Orleans Square opened, “we had a press event, with all the local press covering.” But it wasn’t that big of a deal.

The following year, “We had an opening for the Pirates of the Caribbean the same time as we were opening the Sailing Ship Columbia, which was an additional ship on the Rivers of America. We sailed all the press people around on the ship and then came in and fired the cannons and had a sword fight on the deck.”

In addition, there were buccaneers boarding the ship from smaller craft and pirates falling from the ship into the river during their duels. Once they disembarked the ship, the press crew was led to the entrance of the Pirates attraction, where they “stormed” the door to gain entrance.

“I was in on that,” Charlie said proudly, but humbly.

There would be many more memorable press events in Ridgway’s future, but they would take place some 2,500 miles to the east, in Walt Disney World.

“Charlie had four or five years working with Eddie Meck at Disneyland before he moved to Florida,” Sklar said. “Charlie was part of a group of key Operations staff members who moved to Florida to run Walt Disney World. That was Dick Nunis’ staff — many of them [including Charlie] named Disney Legends after they retired — names like Bob Allen, Carl Bongirno, Bill Sullivan, Bob Matheison and Tom Nabbe.”

Among the first people Ridgway called to lend a helping hand with publicity leading up to WDW’s opening in 1971 was none other than Eddie Meck.

After nearly 20 years with the Walt Disney Company, Eddie Meck passed away in 1973, but his legacy lives on to this day.

“I’m not sure about this,” Sklar said, “but Eddie probably was working right up until the day he died.”

As they say in Hollywood, the show must go on.

Until his death in July 2017, Marty Sklar traveled the length and breadth of the country spreading Disney pixie dust. Do you have any fond memories of seeing him in person at either a book signing or a Disney fan convention? Let us know about your experiences.

You can read more about Marty Sklar in Chuck Schmidt’s “Still Goofy About Disney” blog HERE.

Subscribe to the AllEars® newsletter so you don’t miss any exciting Disney news!

Trending Now

A classic Disney attraction is closing soon!

Universal is growing... but the resort still has some issues.

Let's have dinner at Cape May Cafe at Disney's Beach Club Resort to see if...

Grab these discounted Disney gifts online RIGHT NOW!

We found our new favorite cinnamon roll, and we're obsessed!

These comments on Disney posts seriously made us laugh!

A major renovation is about to happen at Disney's Fort Wilderness Resort & Campgrounds!

As a Disney Pro, I'm always on the lookout for the best Disney souvenirs, and...

Heads up if you're about to stay at the Wilderness lodge for the first time.

LEGO just dropped our favorite set ever!

No matter how tempting it might be to stay in line for Slinky Dog Dash...

Why does this abandoned land sit in the middle of Islands of Adventure?

As a Disney Pro, I'm always on the lookout for Disney essentials, and these are...

Pssst. Hey, we have something new to show you, courtesy of Stitch!

Six Flags has just announced that they're CLOSING on of their theme parks entirely this...

Let's find out what problems Disney Adults have encountered at the Orlando International Airport.

We just got a new update on the Tower of Terror movie!

BREAKING: Spaceship Earth is temporarily closing this summer at EPCOT!

The Frozen Ever After attraction in Disneyland Paris has taken a BIG step forward!

Come with us to Daisy's Dig in Animal Kingdom for Cool Kid Summer!