Sailing vessels – from cartoon props to park attractions to resort launches to majestic ocean liners – have been woven into the fabric of the Disney experience almost from the day Mickey Mouse was created.

Welcome aboard. And watch your head and step as we sail through a history of Disney’s multi-faceted watercraft in a special six-part Still Goofy About Disney series.

ANCHORS AWEIGH

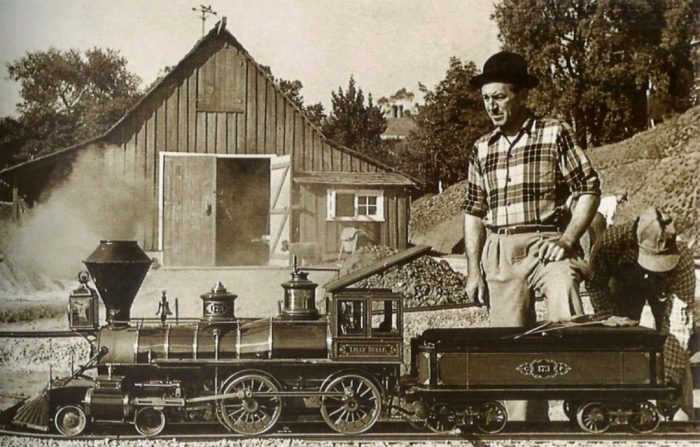

Walt Disney was always known as a “train guy,” his love affair with railroads bordering on unbridled passion. He was mesmerized by the raw power of steam engines, the clanging of steel wheels on steel tracks, and the high-pitched sound of the locomotive’s whistle as it pulled into a station, with puffy clouds billowing from its large smokestack.

There’s a small room tucked near the lobby of the Disney Vacation Club wing at the Wilderness Lodge in Walt Disney World known as The Train Room. It’s here where several miniature train cars that once belonged to Walt are on display, giving guests a glimpse into Walt’s admiration for trains.

Those cars were part of Walt’s own Carolwood and Pacific Railroad, a train layout which took up much of the backyard of his home off Carolwood Drive in the Holmby Hills, located between the tony towns of Bel Air and Beverly Hills in California.

Although the trains were small – one-eighth full size – they were large enough to transport adult riders, assuming they were willing to sit at one end of a train car and prop up their legs at the other end.

In addition to designing each railroad car in exact detail and often working long into the night to maintain them, Walt personally devised a half-mile track layout on his property, even including a tunnel – under his wife Lillian’s flower garden – to add an element of excitement to the journey.

For Walt, his Carolwood and Pacific Railroad served many functions: It was a way to entertain his daughters’ friends, as well as the neighborhood children; it also was a way for him to blow off steam [pun intended]; working countless hours on his model railroad gave him a break from the enormous pressures of running his studio. It also took him back in time to his youth.

Walt Disney grew up with trains. At the tender age of 15, he secured a summer job as a news butcher with the Van Noyes Interstate News Company. He sold newspapers, fruit, candy and soft drinks to passengers during the hours-long train rides through Missouri, Illinois and Kansas, as well as to some faraway places like Colorado.

Several years later, at the tail end of World War I, Walt joined the Red Cross Ambulance Corps in hopes of taking part in the war effort [unlike his brother Roy, he was too young to join a fighting regiment]. Walt’s unit made the trip by train from the Midwest to Sound Beach, Connecticut, where they waited impatiently to be shipped to the front lines in Europe.

But on Nov. 11, 1918, a peace accord was reached – ending the so-called War to End All Wars – and hostilities in Europe drew to a close. With the end of the war, most of the fighting units were now heading back to the United States, but the Red Cross was still needed in France. Walt and his fellow ambulance corpsmen hopped on a train to Hoboken, New Jersey, where a weary-looking former cattle ship was waiting to transport them to France.

It was Walt Disney’s first experience sailing across a vast body of water. Before that, the closest he had come to a large floating vessel was when he and a childhood friend dreamed of sailing down the Mississippi River aboard a paddle-wheeler as they fished along the banks of the fabled waterway.

FAR FROM A LUXURY CRUISE

The voyage over the chilly Atlantic Ocean was far from a luxury excursion – no gentle breezes wafting across the decks, no fruity cocktails, no glamorous evenings with guests dressed in gowns and tuxedos. In addition to carrying the Red Cross volunteers and supplies, the ship, the Vauban, was loaded with something a bit more disconcerting – ammunition – making what should have been a rather uneventful trip quite perilous.

Adding to that angst of the journey was the fact that there were innumerable leftover German mines still lurking in the waters off England and France. With the assistance of several minesweepers, though, the Vauban gingerly made its way through the English Channel to Le Havre, France, where it unloaded its cargo … and scores of relieved passengers.

After a year in France, aiding in the post-war relief efforts, Walt and his Red Cross mates returned to America aboard another veritable floating rust bucket, sailing from Marseilles on the picturesque south of France on the Mediterranean, through the Strait of Gibraltar with African nation of Morocco to the left and Spain on the right, then across the vast Atlantic Ocean to New York City.

It was, by all accounts, a far more peaceful trans-Atlantic voyage back to the United States, particularly since this ship wasn’t weighed down with explosives.

After returning to the Midwest, an older, decidedly more worldly Walt Disney set out to change the course of the entertainment industry.

After many fits and starts, highs and lows and skating in and out of bankruptcy while pursuing his chosen field – animated short films – Walt and his brother Roy reached a level of stability, thanks in large part to the success of a scrawny cartoon mouse named Mickey.

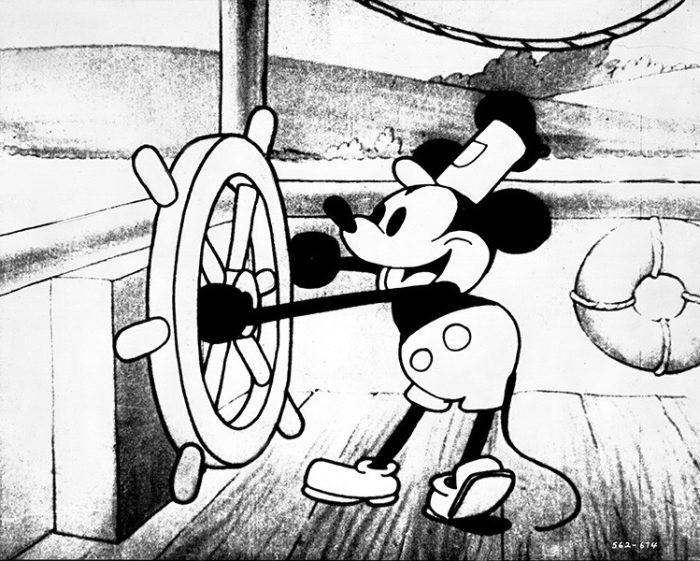

Steamboat Willie, coming on the heels of The Jazz Singer, Hollywood’s first “talking” motion picture, was the first cartoon to successfully blend synchronized sound and a musical score [many attempts at synchronized sound had been made during the 1920s, but the neophyte filmmakers never quite got it right]. Steamboat Willie was a primitive attempt, to be sure, but it was the start of decidedly bigger and better things for the Walt Disney Company.

Steamboat Willie lasted just seven minutes and 42 seconds, but it took months to animate and develop, with the arduous process of incorporating synchronized sound into the finished product being the most troublesome aspect of the film.

During his quest to add sound to Steamboat Willie, Walt spent considerable time in New York City, often spending money that his company didn’t have. Through it all, Walt’s belief in making Steamboat Willie a “talkie” was unwavering.

Walt himself supplied the voices of both Mickey and Minnie [actually, the sounds emanating from their mouths were more whistles, shrieks and shouts than spoken word] as well as the voice of the parrot, who at one point yells: “Man overboard!”

The rickety steamboat drawn by Disney artist Ub Iwerks was as scrawny as Mickey Mouse himself, with a sidewheel propelling it and two giant bouncing and tooting smokestacks.

Steamboat Willie debuted at the Colony Theater in Manhattan on Nov. 18, 1928 [the date now recognized as Mickey Mouse’s date of birth] to resoundingly positive reviews. Billboards for the film read: Disney Cartoons Present, A Mickey Mouse Sound Cartoon, Steamboat Willie. A Walt Disney Comic By Ub Iwerks.

Although there were other attractions on the movie theater’s bill – a stage show and the featured film, a forgettable talkie called Gang War – Steamboat Willie was the talk of the movie world. Decades later, in recognition of its importance in the world of motion pictures, Steamboat Willie was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry, on the basis of it being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

Walt’s gamble on Steamboat Willie paid off handsomely. After tackling synchronized sound and prolifically producing a wide array of talking cartoon shorts, he and his team went on to develop the multi-plane camera technique, which would add life-like dimension to his next big gamble – the full-length animated motion picture Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which opened on Dec. 21, 1937.

It, too, was groundbreaking … and a success beyond Walt’s wildest dreams. The marriage of Mickey Mouse, his new cartoon hero, and a steamboat had truly launched an entertainment juggernaut. As Walt said on many occasions afterwards: “We can’t lose sight of one thing: That it was all started by a mouse.”

But with success came inevitable pressure to build on that success. And, in Walt’s case, with added pressure came signs of mental fatigue. In 1931, he had suffered what he called “one heck of a breakdown.”

ROY SUGGESTS A CRUISE TO EUROPE

A few years later, in the midst of the years-long production of Snow White, Roy saw similar signs that his brother might be headed for another health crisis. Roy suggested that he and Walt take their wives on a well-deserved vacation to Europe.

That trip to Europe saw the Disneys sail on the Italian luxury liner, The Rex. In the coming years, in addition to Europe, Walt and Lillian cruised to the Hawaiian Islands several times.

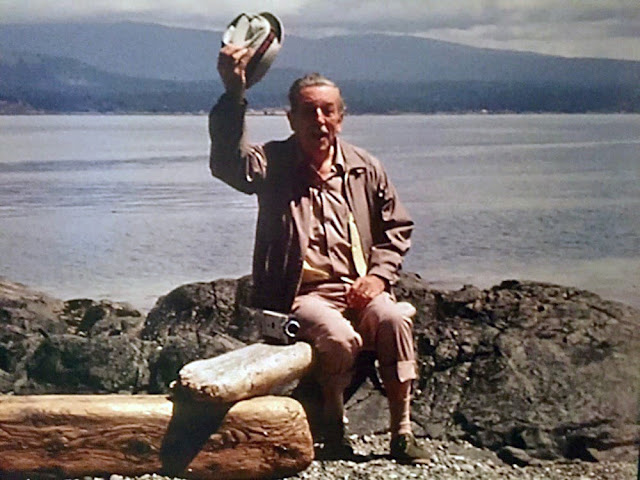

Indeed, Walt and Lillian and various members of their family would enjoy a variety of sea-faring adventures up until Walt’s death in 1966.

In most cases, Walt and Lillian’s cruises were peaceful, relaxing experiences across the Atlantic, the Pacific or through the Caribbean to a variety of touristy ports of call, although the ever-fidgety Walt reportedly had a hard time with the relaxation aspect of sailing. Once they landed, though, Walt was often pressed into making appearances. Indeed, many of his excursions did have a work element attached to them.

On the return trip home, Walt, Lillian and several other members of El Groupo opted to take a 17-day cruise aboard the Santa Clara from the west coast of Colombia, through the Panama Canal and up the East Coast to New York City. While in the Big Apple, Walt and his party attended the opening of the soon-to-be Disney classic Dumbo.

In 1949, Walt and Lillian and their daughters Diane and Sharon sailed on the Queen Elizabeth ocean liner for a trip to England. It was another working vacation – Walt was going to England to check in on the filming of the Disney film Treasure Island, the first Disney live-action film without animation.

Other “vacations” saw them visit places such as Switzerland, where they checked out a new wave-making machine, and to Munich, Germany, which had a working “moving sidewalk” Walt was interested in seeing.

In the early 1960s, Walt, Lillian and their friends, architect Welton Beckett and his wife, sailed throughout the West Indies, stopping at a few small Caribbean islands. On one island they visited, near Cuba, was a one-time pirate hangout; the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction is said to have sprung out of that visit. And, while in Puerto Rico, Walt purchased a mechanical bird in a cage, which served as inspiration for the Enchanted Tiki Room attraction.

During the trip, Walt took time to work on his “latest and greatest dream” – the Florida Project, and his vision for a city of the future: EPCOT. There were other projects in the works as well, including the Mineral King Resort, which was a failed attempt to develop a ski lodge in the California mountains.

The family boat trip around British Columbia would be Walt’s last voyage; he died five months later.

FIRST IN A SIX-PART SERIES. Next: When Disneyland opened in 1955, it was a place without peer. It also featured several piers, where guests could climb aboard a boat and sail off on an unforgettable adventure.

Chuck Schmidt is an award-winning journalist who has covered all things Disney since 1984 in both print and on-line. He has authored or co-authored seven books on Disney, including his Disney’s Animal Kingdom: An Unofficial History, for Theme Park Press. He also has written a regular blog for AllEars.Net, called Still Goofy About Disney, since 2015.

Trending Now

Get over to BoxLunch NOW!

Let's have a chat about an Oura Ring that Disney Adults just can’t seem to...

Have you seen Disney Visa's newest Disneyland 70th card design?

Going to Disney World alone isn't as scary as you'd think...

July is here! Can you believe we’re now onto the back half of the year?!...

This MagicBand+ hack can make a world of difference during your next Disney World trip!

There are plenty of airports to choose from when flying to Disneyland!

Universal is growing... but the resort still has some issues.

Wait times in Disney World the day AFTER the 4th of July are NOT what...

Here are the park bag mistakes you might make when going to Disney World and...

Grab these discounted Disney gifts online RIGHT NOW!

How are Disney fans really feeling about the new version of Test Track? Tell us...

Amazon Pride Day deals are starting, and now's your chance to get Disney essentials on...

Let's have dinner at Cape May Cafe at Disney's Beach Club Resort to see if...

It all starts on July 8th!

You might want to AVOID buying Disney World Lightning Lanes on these days in July.

We know, we know — it’s still summertime, but it’s always a good time to...

We can't get over this one...

We went to Black Tap Craft Burgers & Shakes at Downtown Disney at Disneyland Resort...

Ever wondered what Disney World crowds are like on the Fourth of July? We've got...