If you’ve ever watched a movie or television program that shows panoramic views of the city of Los Angeles, there’s a good chance you’ve seen the distinctive Capitol Records building.

That structure, which opened in 1956, looks very much like a stack of record albums piled one on top of another. To be sure, it was quite a different spin on architectural design.

The Capitol Records building was designed by Welton Becket and Associates. During his lifetime, Becket and his firm oversaw the design and construction of more than 100 projects worldwide, many of which were award-winning and iconic.

Becket first made a name for himself in 1933 when he and former college classmate Walter Wurdeman joined forces with Charles Plummer to form the Los Angeles-based design firm Plummer, Wurdeman and Becket.

One of the upstart company’s first major projects was the design of the Pan Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles, which opened to rave reviews in 1935 and served as the city’s premiere indoor entertainment venue for several decades.

The structure was noteworthy for its Streamline Moderne design.

To the uninitiated, Streamline Moderne is an international style of Art Deco architecture and design that emerged in the 1930s. It was noteworthy for its aerodynamic properties. Streamline Moderne places an emphasis on curving forms, long horizontal lines and sometimes nautical elements.

It was employed in the design of a wide variety of applications, including railroad locomotives, automobiles, buses, buildings, telephones, toasters, household appliances and other devices to give the impression of sleekness and modernity.

Why is all this relevant to Disney? Well, the next time you walk into either Disney’s Hollywood Studios or the Disney California Adventure, take note of the design of the main gate entry structures. That’s what classic Streamline Moderne looks like.

According to “The Imagineering Field Guide to Hollywood Studios” [Disney Editions]: “The curvilinear leading edges of the spires atop the roof canopy echo the forms of contemporary aircraft design, and the fins that repeat below are a recurring motif found in much of the automotive design of the time. The clean lines offer a timeless quality that allows the style to hold up as an entry statement all these years later.”

Walt Disney and Welton Becket were good friends who often vacationed together with their wives. One notable trip took them to an island off Cuba, which is said to have served as the inspiration for the Pirates of the Caribbean attraction.

Becket was instrumental in persuading Walt to form WED Enterprises, the forerunner of Walt Disney Imagineering, when Walt was in the early planning stages for Disneyland.

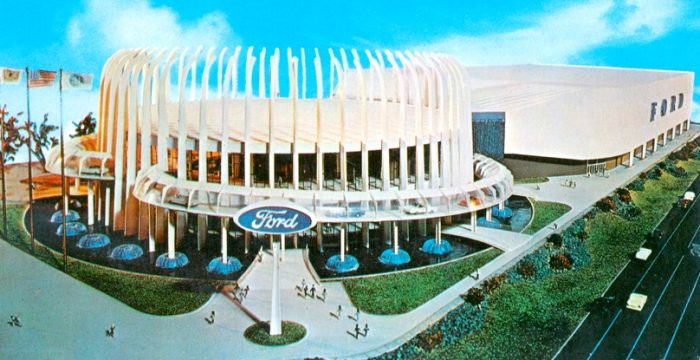

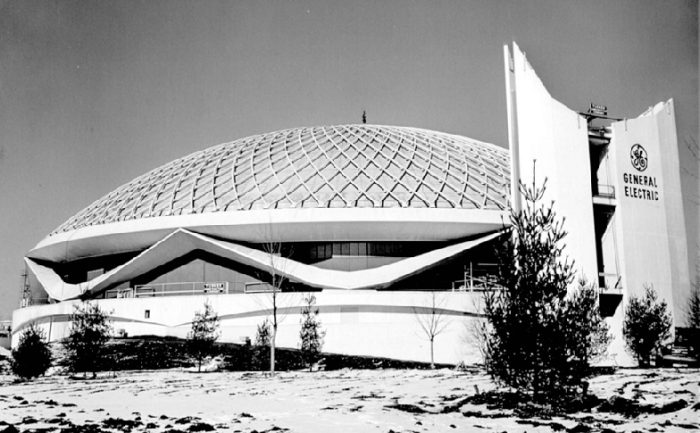

In the early 1960s, Disney commissioned Welton Becket and Associates [both Plummer and Wurdeman had passed away by then] to design the pavilions for the Disney-created General Electric and Ford’s Magic Skyway attractions at the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair.

The GE pavilion featured a circular design to accommodate the rotating Carousel of Progress attraction, while the Ford pavilion was somewhat elongated to allow for straightaways for the time-traveling Ford automobiles used in the show.

Both buildings were eye-catching and iconic, but sadly, they were demolished after the Fair closed in the fall of 1965.

A few years after the World’s Fair, when plans to build an East Coast Disneyland were being finalized, Disney again commissioned Becket and Associates to design both the Contemporary and Polynesian resorts.

While both resorts were designed by Becket and his team, construction was handled by U.S. Steel.

The Contemporary was designed as a 14-story building in the shape of an A-frame. As part of its enduring appeal, monorail beams run through the heart of the building.

In a unique twist, modular guest rooms for both the Contemporary and Polynesian resorts were assembled off-site, with everything – furniture, plumbing, doors – clamped down.

When completed, the rooms were shipped to WDW property, where they were raised by cranes and slid into the A-frame, much like a chest of drawers.

The idea was to give Disney the flexibility to remove the rooms after a certain amount of time and replace them with updated versions.

Unfortunately, the weight of the buildings saw them “settle” in the soft Florida soil and the modular rooms were unable to be removed.

When Disney decided to build a third theme park at Walt Disney World in the late 1980s – the Disney/MGM Studios, now Disney’s Hollywood Studios – the idea was to showcase the world of entertainment … giving guests a peak at what went on behind the scenes during the production of films, television shows and music that so embody pop culture.

In addition, the Disney/MGM Studios wanted to celebrate “the Hollywood that never was and always will be.” What better way to do that than by resurrecting the Streamline Moderne architecture so popular during Hollywood’s “golden age”?

The Studios’ main entry portal, as well as the automobile back entrance to the park, were designed in classic Streamline Moderne style.

Walt Disney himself was no stranger to Streamline Moderne. When plans were being developed for a new Disney animation studio in Burbank in the late 1930s, Walt worked with furniture and industrial designer Kem Weber – a key proponent of Streamline Moderne architecture – in designing the interior and exterior spaces of the studio. Weber even went as far as to design specialized furniture for Walt’s animators.

Several years after Disney California Adventure opened in 2001, the powers that be at Disney decided that a do-over was in order. If you recall, the park’s original main entrance featured giant letters spelling out C-A-L-I-F-O-R-N-I-A.

There also were murals of mountains, a giant sun wheel and a replica of the Golden Gate Bridge, which saw the Disneyland monorail cross over every few minutes.

“The choice of the architectural design for the entry statement to DCA reflected what was established in Los Angeles at the time of Walt’s arrival,” said Kevin Rafferty, retired creative executive director for Walt Disney Imagineering.

“That Streamline Moderne design style was popular and predominant in L.A. at that time, such as in big downtown department stores (you can see the similarities at DCA), restaurants and hotels.”

Even though Streamline Moderne architecture peaked in the 1930s, it lives on at several Disney properties – as does the design influence of Welton Becket.

Chuck Schmidt is an award-winning journalist and retired Disney cast member who has covered all things Disney since 1984 in both print and on-line. He has authored or co-authored seven books on Disney, including his On the Disney Beat and Disney’s Dream Weavers for Theme Park Press. He has written a regular blog for AllEars.Net, called Still Goofy About Disney, since 2015.

I thought the idea that the rooms at the Contemporary could be removed was an urban legend… it’s been covered elsewhere and was thoroughly debunked as it was always known the rooms would “settle”.

Fantastic article. Thanks!