The Walt Disney Company has been a money-making juggernaut for decades, what with its theme parks, movies, television shows, a cruise line and Broadway shows. Partnering with Marvel, Pixar and Star Wars more than a decade ago has only solidified the company’s status as a Wall Street darling.

But it wasn’t always that way.

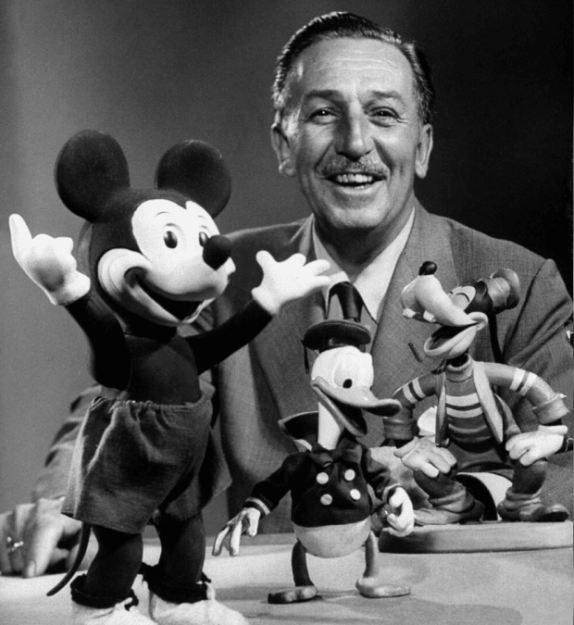

Although Walt Disney’s imagination knew in bounds, he always seemed to be walking a financial tightrope, teetering precariously on the brink of bankruptcy on several occasions.

When Walt began his long, winding and often difficult journey into the world of entertainment, money – or lack of it – was always his biggest stumbling block.

“I’d say it’s been my biggest problem all my life – it’s money,” Walt said. “It takes a lot of money to make these dreams come true. Make no mistake. It takes money to fail AND succeed.”

Even when the technology of the day hadn’t yet caught up to Walt’s fertile mind, he forged ahead with his seemingly pie-in-the-sky ideas, always maintaining a “yes we can” attitude. Although “damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead” is attributed to Admiral David Farragut during the Civil War, it was very much Walt Disney’s mantra as well.

Walt had more than enough ideas, talent and ambition to succeed. He just never seemed to have enough financial backing to support all of his grandiose ambitions.

And Disney, being a smart businessman, seized the opportunity.

The first offer came from the George Borgfeldt Company of New York, which signed a deal with Disney to manufacture and sell figures, apparel and toys involving Mickey and Minnie Mouse, with Disney receiving a percentage of the profits. The first item to be manufactured by Borgfeldt were Minnie and Mickey handkerchiefs.

Another offer came from King Features, who wanted a comic strip to run nationwide in newspapers. Walt assigned Ub Iwerks, his most trusted animator, to devise the Mickey Mouse strip, which debuted on Jan. 13, 1930. The strip proved to be so popular that King Features began syndicating the comics in color for Sunday newspaper supplements on Jan. 10, 1932.

Also in 1932, a young hat salesman and advertising executive from Baltimore had the idea that he could turn the Disney Studios’ scrawny “leading man” – the cartoon character Mickey Mouse – into a bona fide, revenue-generating superstar. He placed a phone call to California and set up a meeting with Walt and his brother Roy.

After a two-day train ride, Kay Kamen arrived in Los Angeles brimming with ideas on how to better market Mickey and the Disney brand. The brothers Disney were so impressed by Kamen and his marketing strategies, they signed him to a contract and named him the company’s sole licensing and marketing representative. They were impressed by Kamen’s insistence that the products sporting the Disney name would be of high quality.

Another endorsement came on General Foods’ cereal boxes. Kids [more correctly, their parents] were asked to buy Post Toasties cereals and there would be free cut-outs of Mickey and his pals on the boxes as a special treat [remember, the United States was in the throes of the Great Depression, so combining food with an entertainment aspect was nothing short of genius].

“I’m on Post Toasties boxes now!” proclaimed Mickey [and later Minnie] in a nationwide newspaper ad campaign dreamed up by Kamen. “Here’s a barrel of fun for boys and girls! Wonderful cut-outs of Mickey and his pals are on some Post Toasties packages. The Three Little Pigs on others. Children love them!

“Serve Post Toasties often! The whole family will love these golden, corn-heart flakes that stay crisp and crunchy in milk or cream. A product of General Foods.”

The Kamen-Mickey Mouse partnership had far-reaching implications – so much so that several companies on the brink of bankruptcy managed to pull themselves into solvency thanks to the association.

The Ingersoll-Waterbury Company of Connecticut was also on the brink of bankruptcy in the early 1930s when it signed an agreement with Kamen and Disney to manufacture Mickey Mouse watches. In the span of two years, the company sold 2.5 million watches and left bankruptcy in the dust.

The profits generated by Kamen’s savvy business maneuvers enabled Walt Disney to do what he often did: Reinvest the money he’d just earned into another project, something bigger, grander … and even more financially challenging.

His biggest gamble to date turned out to be Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the movie industry’s first full-length, animated feature film. The film’s monumental success catapulted Disney from small-time player into the lucrative realm of major motion picture studio.

Other successful feature films followed, permitting Walt to dream the impossible dream of creating a themed amusement park where parents and children could have fun together. Once again, his lofty ambitions would be costly. And again, Walt and his trusted lieutenants came up with strategies to help turn near financial ruin into monetary buoyancy.

About a decade later, Walt Disney pulled off another savvy business maneuver when he signed on to create four attractions for the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair.

“What we didn’t realize at the time was that Walt had written into each of the contracts for the World’s Fair shows that Disney owned them,” said former Imagineering leader Marty Sklar. “Every one of those shows came back to Disneyland.

“And all those new attractions were paid for,” including the cost of trucking them across country to Disneyland.

Not only were the Fair shows paid for by corporate sponsors, but they were guaranteed hits for Disneyland, having been tested over two years and given a rousing stamp of approval by an always-demanding East Coast audience.

Perhaps Disney’s biggest outreach to corporations came during the planning stages for EPCOT.

Preliminary plans for EPCOT called for a variety of nations hosting pavilions to showcase their cultures, lifestyles and wares. But even that simple idea met with resistance.

“Unfortunately, there’s an organization called the Bureau of International Expositions (BIE) and their rules are that no country tied to their organization can be in a permanent world’s fair, if you will, or expo, for more than a year,” Sklar said of the first big hurdle Disney had to overcome.

That rule “virtually eliminated countries from participating. If you notice, you don’t see any flags flying in front of countries in the World Showcase,” Sklar said. “There’s no nation representation.”

To get around the BIE’s rules, Disney executives went to major corporations within a variety of countries to get them to pony up money. “That’s why you see all those corporate sponsorships in each of those pavilions,” Sklar said.

Once that dilemma was solved, a bigger question arose for Sklar: “How do we pay for all this?” meaning all of EPCOT. As Walt Disney said when he bankrupted himself in creating Disneyland: “These ideas cost a lot of money.”

Remember, at about the same time EPCOT was being conceptualized, Disney was about to partner with the Oriental Land Company to build Tokyo Disneyland. Disney’s purse strings were being stretched to the max.

The answer? Corporate sponsorship.

“I went to [then-CEO] Card Walker, who was a marketing man from his experiences with the studio, and we decided to go back to the whole idea that Walt had said, that no one company can do this by itself,” Sklar said. “And that’s when we started going out to all the big corporations and said, ‘OK, here’s what we’re planning to do and we want you to be part it.’”

Getting American industry to fall in line “was a huge selling job,” Sklar remembered.

A team of Disney’s top executives at the time – Sklar, Walker, Donn Tatum, Dick Nunis and Jack Lindquist among them – began a veritable blitz of America’s top companies, giving in-depth presentations on why these corporations should be involved in Disney’s EPCOT project.

The presentations were designed by John McClure Sr., one of Hollywood’s leading art directors and the designer of the Hall of Presidents attraction at Walt Disney World. One of the first presentations, which lasted two days, was to General Motors, which ultimately was happy to get involved by sponsoring a pavilion at EPCOT [World of Motion].

“That broke the dam, if you will, and Exxon was right behind them,” said Sklar.

“These projects are so expensive,” he added. “Without the sponsors, particularly in those days, you couldn’t do those kinds of things. Disney didn’t have the wherewithal to finance something like that by itself.”

“There were a lot of visionaries in the companies that we dealt with who rolled the dice with us,” Sklar added.

To this day, corporate sponsorship plays an integral role in the Disney parks’ scheme of things.

“Presented By,” “Compliments Of” and “Hosted By” are phrases that you’ll see on signage throughout Disney parks.

It’s not uncommon to see names like Coca-Cola, Joffrey’s, Enterprise, Cuties, Dreyer’s, Edy’s, Mars Wrigley, Hallmark, Sara Lee, Frito Lay, Nestle, Kraft and Dole appear on either attraction queue entrances or in dining areas.

Even park guide maps have featured corporate backing. In the early days of Walt Disney World, the maps were sponsored by camera and film giant GAF. Years later, Kodak took up the sponsorship.

Delta Airlines took over sponsorship in 1989 with a revamped attraction called Delta Dreamflight. The site currently houses Buzz Lightyear’s Space Ranger Spin.

Chuck Schmidt is an award-winning journalist who has covered all things Disney since 1984 in both print and on-line. He has authored or co-authored seven books on Disney, including his On The Disney Beat, for Theme Park Press. He also has written a regular blog for AllEars.Net, called Still Goofy About Disney, since 2015.

Trending Now

Get your calendars out; we know when Disney World Christmas party tickets go on sale!

Amazon is clearing out the Disney vault!

Amazon has Loungeflys on sale as part of Prime Day!

Donald Duck is back in his official meet and greet spot in EPCOT!

Let's breakdown the major changes coming to Disney World this Fall 2025.

Amazon Prime Day is here with some HUGE deals on Disney souvenirs.

We asked our resident Disney adults which ride at Hollywood Studios they would rope drop...

Here's what you've gotta know about Disney World's "Other" Airport!

The holiday dates can be confusing for Disney World, so we're going to break it...

Everyone say hello to Whimsy!

Disney's Boardwalk Villas got a scathing review recently that could indicate some issues with a...

Let's have a chat about an Oura Ring that Disney Adults just can’t seem to...

Big update from this Disney World ice cream spot -- getting sundaes just got a...

Here's why you might want to skip your visit to Disney World this year.

Fans are BEGGING Disney to bring back this classic ride, but the wait isn't likely...

Bad Florida weather is creating some new problems at Disney World.

Amazon Prime Day is giving us amazing deals on Oura Ring accessories!

Don't make these mistakes when planning your dining in Disney World!

Should this iconic Hollywood Studios symbol be moved or stay in its original location?

Is Disney World FINALLY evening out after weeks of being on the struggle bus? We...