Before there was Walt Disney World, Tokyo Disneyland, Disneyland Paris, Hong Kong Disneyland or Shanghai Disneyland, there was just little, ol’ Disneyland in Anaheim, Calif.

Although Walt Disney detested doing sequels to his movies, he wasn’t averse to creating a second Disneyland. In the years following the opening The Happiest Place on Earth in 1955, there was some talk, both from within the company and from outside sources, that building a sequel might not be a bad idea.

It’s still hard to imagine, given the success of Disney’s theme parks worldwide today, but Walt and many of his top lieutenants had some doubts about building a second Disneyland east of the Mississippi River. Specifically, it was thought by many that Disneyland was a West Coast phenomenon and Disney’s brand just wouldn’t be very successful on the East Coast.

In 1960, a group of businessmen from St. Louis approached Disney about building a second Disneyland in the city known, ironically, as The Gateway to the West. Disney looked at the possibility long and hard, but after months of haggling, “Some key person backed out,” according to Disney Legend John Hench, and the idea of a St. Louis Disneyland faded.

Still, Walt couldn’t get the idea of heading East out of his mind. He needed something to convince himself that making a bold move East would be viable. So when the opportunity arose to participate in the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair, Walt jumped at the idea.

Walt Disney’s ties to international expositions go all the way back to the 1893, when his father, Elias Disney, worked as a carpenter at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

And at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair, Disney characters Mickey, Minnie and Pluto starred in a five-minute Technicolor cartoon named Mickey’s Surprise Party.

In 1958, Disney decided to test the waters on an international scale, setting up a show at the World’s Fair in Brussels, Belgium. According to Disney Legend Bob Gurr, “Walt was always thinking ahead of things. He sent a lot of guys over there [to Brussels] to sort of case the joint, to see what was involved.”

At the Brussels World’s Fair, Disney’s then-innovative 360-degree Circarama film America the Beautiful played to packed houses. It was the first Disneyland-style attraction to be shown outside the United States.

Then, in 1962, “Walt sent a bunch of us to the Seattle World’s Fair for the same reason,” Gurr said. By “casing the joint,” Walt was able to get a good idea of what would work and what wouldn’t work at a World’s Fair … setting the stage for one of the biggest gambles of his life: The Walt Disney Company’s participation at the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair.

When Robert Moses and the folks at the New York World’s Fair came calling, the wheels began turning in Walt’s head. By participating in the Fair, Walt figured, he could resolve, once and for all, the question of whether his style of entertainment would be popular with East Coast audiences. And if Mickey and Friends were a hit in New York City, maybe … just maybe … Disney could make the move East on a permanent basis.

“The New York World’s Fair was critical, because Walt used it as a proving ground for Walt Disney Imagineering to develop bigger and better shows and to advance animatronics beyond the [Enchanted] Tiki Room,” said Tony Baxter, Imagineering’s former senior vice president of Creative Development.

“I consider the Fair to be the first golden era of Imagineering attractions. New ride systems and sophisticated Audio-Animatronics were developed for the Fair. It was a giant leap forward in what could be done [in Disney’s theme parks].”

But over and above that, Walt wanted to see first-hand the reactions of Easterners to those attractions. To paraphrase Frank Sinatra, if Disney could make it in New York, it could make it anywhere. As it turned out, that anywhere became a huge tract of land south of the then-sleepy town of Orlando, Fla. When the Fair opened on April 22, 1964, Walt was already secretly scooping up property in central Florida.

In a stroke of pure business genius, Walt enlisted corporate sponsors pay for each of Disney’s four Fair attractions. Moreover, according to former Imagineering leader Marty Sklar, when the Fair closed, those same companies paid for the attractions to be shipped back to Disneyland, where they took up residence in whole or in part [it’s a small world and some of the dinosaurs from Ford’s Magic Skyway can still be seen in the Happiest Place on Earth].

Sklar traces Disney’s participation in the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair back to 1957. “It started, I guess, with Abraham Lincoln,” he said. “That show had been written – not the single Lincoln, but the entire Hall of Presidents show – in 1957.” The problem was, technology hadn’t yet caught up with Walt’s wildly creative imagination.

But when Moses, the president of the Fair, saw mock ups of the Hall of Presidents show during a tour of the Disney Studios, he was insistent that Disney bring it to the Fair. “But Walt said, ‘We haven’t done one figure yet,” Sklar said. “Ultimately, Moses put Disney and the state of Illinois together,” which resulted in the Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln presentation at the Illinois state pavilion.

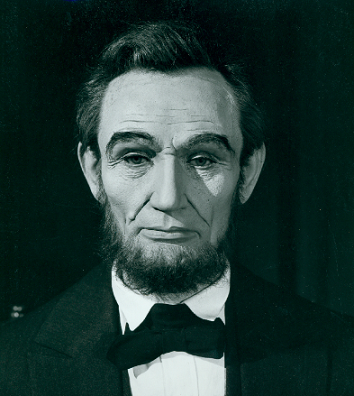

The Lincoln show was ground-breaking on so many different levels. To begin with, Disney’s creative team had to make their recreation of Honest Abe look like an honest to goodness Abraham Lincoln. Anyone with a penny or a five-dollar bill in their pocket could easily compare the facial features on the currency with the Audio-Animatronics figure on stage. Abe had to be spot-on … and he was, thanks to the work of sculptor Blaine Gibson.

And then there were the movements of the robotic figure positioned in the center of the stage. No one had ever tried, much less succeeded, in having a life-size animated figure move with the fluidity of a human being. The system used hydraulic and pneumatic valves to achieve that realism.

“It was a marvel the machine worked as well as it did from the get-go,” said Disney Legend Bob Gurr, who was the main man behind the development of Audio-Animatronics. “It combined the sculpting, the skin, the detailed facial animation, animated hands, plus the body, plus getting him up out of the chair and all the electronics to do with that … it was a big effort by so many people working on that machine.”

The show began with the Lincoln figure seated at center stage. Then, to the amazement of those in the audience, Lincoln would rise up from the chair, stand and begin to recite lines from some of his most famous speeches. Gurr called Lincoln’s rise from the chair “that trick thing.”

The success of the development of the Lincoln figure in the years prior to the Fair’s opening allowed Gurr to devise a system where Audio-Animatronics figures could be mass-produced.

“Within a year, we found with the basic concept of Lincoln we could actually engineer what we would call production parts,” Gurr said. “In other words, instead of making a part one at a time, we could make a whole group of parts. By investing in the tooling to make parts, we could manufacture humans and animals out of all these standardized parts. All of this started with the basic configuration of Abraham Lincoln.”

Gurr and the rest of the creative team used this philosophy to build Audio-Animatronics figures for Disney’s three other World’s Fair shows: Ford’s Magic Skyway, General Electric’s Carousel of Progress and Pepsi-Cola’s it’s a small world.

The Magic Skyway show took guests, seated in authentic Ford Motor Company cars [sans engines and transmissions and all convertibles, so guests wouldn’t hit their heads] on a journey through time, from the dawn of the ages to prehistoric times and then into the future [a subtle hint at Walt’s desire to build a city of the future]. In addition to contributing to the development of the massive dinosaur figures seen during the ride, Gurr was the chief designer for the actual ride system which carried the cars on their voyage through time.

Borrowing from the booster brake system he and Arrow Development employed on Disneyland’s Matterhorn Mountain attraction, Gurr positioned small one-horsepower gear motors with rotating 16-inch wheels several feet apart along the ride’s two tracks. The wheels [there were a total of 714 of these motors embedded in the two tracks] would come in contact with metal plates attached to the underbellies of the cars, allowing them to move at a slow, but steady pace. [A similar technology is used in the WEDway PeopleMover attraction in Walt Disney World. It is often mistaken for the Omnimover system, where ride vehicles can pivot and traverse up and down inclines.]

Between the 1964 and 1965 seasons, Ford CEO Henry Ford II asked Walt Disney to record the narration for the attraction. Although “Walt had a terrible cough and kept blowing the lines,” said Marty Sklar, “and it took a long time, we finally got a great take.” It seems Walt also had problems pronouncing the names of many of the dinosaurs on display during the ride.

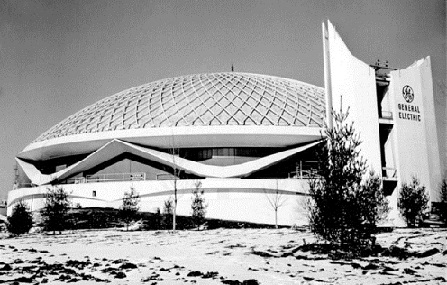

GE’s Carousel of Progress showcased the advancement in electricity from the early 1900s through “modern times” … or at the least, the mid-1960s. There even was a demonstration of nuclear fusion inside the pavilion.

In addition to the 32 Audio-Animatronics figures used in the four-part presentation, Disney employed a carousel-type system to present the show. There were four fixed stages representing different eras in the advancement of electricity and the audience revolved around each different set, with the song “There’s a Great, Big Beautiful Tomorrow” playing every time the audience rotated to a different scene.

The Carousel of Progress remains a popular attraction; it’s located in Tomorrowland in the Magic Kingdom at Walt Disney World.

The it’s a small world attraction is a mainstay at every Disney park worldwide, primarily because of its message of international peace and harmony, particularly among young people.

Although not as complex, Audio-Animatronics technology was used on the dozens and dozens of dolls on display during The Happiest Cruise That Ever Sailed. Gurr, although tied up with the Audio-Animatronics and ride systems on the other three Disney Fair attractions, made contributions to it’s a small world, specifically working with Arrow Development to come up with the system that gently pushed the boats through the narrow canals.

Of course, the most memorable aspect of it’s a small world is its theme song, written by Dick and Bob Sherman. According to Marty Sklar, it’s a small world is his all-time favorite Disney attraction. “The line in that song … There’s just one moon and one golden sun and a smile means friendship to everyone … what a wonderful world this would be if we could follow those feelings.”

In the end, Disney’s participation in the 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair proved to be a huge success, proving once and for all that the Disney brand of entertainment would be a big hit just about anywhere in the world.

Many thanks for this great article!! Do we have any idea how much money Disney was paid to create the World’s Fair attractions?

Regarding Wozz’s post: If I’m not mistaken, part of the deal with developing an eastern Disneyland in St. Louis was that Anheuser Busch would be a major sponsor. That, of course, came with the demand that their beer be sold in the new park. As he was in Anaheim, Walt stood fast in his opposition to that idea and the negotiations broke down.

John … Disney also wanted to build a year-round destination resort. As we know, weather in St. Louis can be pretty harsh in winter. So whether it was alcohol or snow, Disney and St. Louis seemed destined to fail, even with the big bucks Anheuser Busch likely would have kicked in. Chuck

Thanks for a great article !

I have always heard that Disney was pretty close to building in St Louis. Something about alcohol being sold/ not sold changed his mind. I forget all the details. Besides, have you seen downtown St. Louis today? Yikes!!

Disney likely would have pulled out of St. Louis for the very reason they didn’t want to put a second Disneyland on the grounds of the 64-65 NY World’s Fair [the idea was briefly on the table] … winter weather. The plan all along was to build a year-round resort. Thanks for writing. Chuck