Walt Disney World Chronicles: Before Orlando Was Chosen

By Jim Korkis

Disney Historian

Feature Article

This article appeared in the October 2, 2018 Issue #993 of ALL EARS® (ISSN: 1533-0753)

Editor’s Note: This story/information was accurate when it was published. Please be sure to confirm all current rates, information and other details before planning your trip.

Some Disney fans just take for granted that Orlando, Florida, was meant to be the home of Walt’s second theme park. As we approach the 50th anniversary of the October 1971 opening of Walt Disney World, I thought we’d look at the many other places Walt considered before finally settling on Orlando.

There were hundreds of places asking for new Disneylands. In fact, one Disney executive affirmed there were at least 500 by the 1960s.

“We had them from all over,”Walt told interviewer Pete Martin in 1956.” Even from all over the world. They wanted us to do one in Egypt. They wanted us to do one in Japan. They wanted us to do one in Brazil — at the capital there.”

Walt began looking for a possible East Coast spot to build another entertainment venue that would be equivalent to Disneyland, but not just a clone.

When Disney moved its weekly television show from ABC to NBC, General Sarnoff, the president of the network, arranged a meeting with Walt in the Burbank NBC offices.

He was hoping to convince Walt to not only move the show, but to build another Disneyland in Jersey Meadows, a few miles west of New York City in New Jersey.

In fact, Sarnoff had paid for a feasibility study to show it was a great location. Walt, however, had his own person, Harrison “Buzz” Price do another study.

Price’s study showed that tourism in New York was different, with most visitors just coming for a short business trip. In addition, NBC wanted to be a permanent partner, not like ABC who agreed to sell back its investment within the first few years.

Another part of the problem with any East Coast park was that because of the weather it could not stay open year-round, but only about 120 days of the year — just like other amusement parks in the same area.

Walt’s older brother Roy O. Disney recalled: “Walt gave the Meadows proposal a careful look, but he finally decided that there would have to be some method of controlling the weather — a vast dome or some such thing. When the financial backers looked into the cost of such an undertaking they lost their courage pretty fast.”

In 1963, Walt also looked at the Seagram Tower on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls. That observation tower was a tourist spot at the Horseshoe Falls where people could be amazed at the power and beauty of the water.

It became apparent there was not enough room for an entire park, so the discussion turned to installing something like the Disneyland Flight to the Moon attraction in a lower floor of the existing tower.

Walt suggested installing a version of Disneyland’s Circle-Vision, with a film focused on Niagara Falls. However, the film would cost more than $2 million to produce, in addition to the cost for the theater, and so the discussion ended.

NBC/RCA attempted once more to convince Walt to partner with them on a theme park, but this time in Palm Beach, Florida. John D. MacArthur had become a billionaire as the head of Banker’s Life Insurance and RCA. He owned huge tracts of land in Palm Beach, which would solve the weather problem.

However, Walt’s vision had expanded and he wanted not just a greatly expanded entertainment venue but a city with new urban technology to house roughly 70,000 people.

He would later revise that figure to 20,000. The park would be interconnected with the city and surround the park so Walt could control the total environment.

Price’s study indicated that an East Coast park would not have a negative impact on Disneyland and might even bring in West Coast tourists if the park had some significant differences.

Unfortunately, RCA suffered some financial difficulties so it could not afford the cost. MacArthur, who was highly eccentric, became deeply offended when the Disney brothers tried to negotiate for more land as the negotiations were being finalized.

The most impressive project, though, and the one that was almost completed, was Walt Disney’s Riverfront Square in St. Louis, Missouri.

According to Disney urban mythology, Walt walked away from that project over a dispute of the city wanting him to sell alcohol there.

That resulted in him then deciding to go with another location in Central Florida. Actually, as amazing as it might seem, Walt felt he could build both entertainment venues in Missouri and Florida at the same time!

The city of St. Louis had been founded in 1764 and in the early 1960s plans were made to celebrate its upcoming bicentennial with the building of the Gateway Arch (opened October 1965) and the multi-purpose Busch Memorial Stadium (opened May 1966).

Part of the planning for the stadium included setting aside some land just a few blocks to the north to be called Riverfront Square, an outdoor mall about 300 feet long, that would be developed with theaters, restaurants and stores, excluding all automobile traffic.

In 1963, business and civic leaders approached Walt with the proposal that he produce a Circle-Vision travelog film to honor the city’s history as part of the celebration. Walt and his wife Lillian visited the city, but secretly Walt assigned Buzz Price to do a feasibility study about potential visitors to the revived area and how much they might spend.

The CCRC (Civic Center Redevelopment Corporation) was surprised when it asked Walt to be a consultant and it turned out that Walt was interested in doing the entire venue himself even though he was working on projects for the 1964-65 New York World’s Fair.

On March 16, 1964 at a press conference, Walt announced he had refined his ideas into a single, five-story (one-story or more would be underground since they could dig at least 112 feet), enclosed building covering two city blocks. It was enclosed so that it could operate year-round despite the weather. Conservatively, the cost for the project was $40 million and with expectations of at least 25,000 guests per day.

In terms of the sale of alcoholic beverages, Walt proposed an observation floor that could be entered directly by special elevators, avoiding the amusement areas, and feature a formal restaurant, banquet space and a 150-seat cocktail lounge. All those areas would sell beer, wine and alcohol, but would be restricted to adults. The amount of alcohol for each individual could be monitored if they wanted to go into the amusement area.

The general concept was that half of the 600-foot, 3.5-acre building would represent St. Louis at the turn of the century (early 1900s) and the other half New Orleans before the Civil War (approximately 1850). Plans were constantly changing, but here are a few of the ideas that appeared on blueprints.

A Bayou Boat Ride would take guests through a Louisana swamp and down a waterfall into the lower basement 60 feet high and then back up a waterfall at the end. It didn’t feature pirates, but did include alligators and other wildlife. There would also be a “Jean LaFitte Adventure Ride” themed to New Orleans pirates that in later plans were combined with this Bayou Boat Ride.

A Haunted House would have included a stretching room to take guests to a lower floor for a “room of illusions,”but some of the ghosts would be themed to actual Missouri ghost tales. The French Quarter would include restaurants (including a full-sized steamboat in an indoor lake), shops and even a live show.

The St. Louis section would include a Circle Vision theater that featured a 15-minute film that showed a trip down the Mississippi River, perhaps ending with a helicopter trip through the Arch.

Walt also had plans for the Old Opera House to feature a live action show inspired by the Golden Horseshoe Revue in Disneyland, but somehow themed to St. Louis and specifically including French can-can dancers.

There were plans for Fantasyland dark rides like at Disneyland and the placeholders on the blueprints were Peter Pan Flight (the most popular of the Disneyland dark rides) and either Snow White Adventures or a new attraction based on the adventures of Pinocchio.

One suggestion was a gentle roller coaster thrill ride through Mississippi River caves while another was a more leisurely Native American canoe ride, perhaps using the legends of Davy Crockett and Mike Fink.

Imagineers suggested a show with audio-animatronics figures more closely aligned with Missouri, including Thomas Jefferson and Napoleon discussing the Louisiana Purchase, Will Rogers, John Phillips Sousa, and Charles Lindbergh and his Spirit of St. Louis plane among others.

It would be presented in a theater with multiple revolving stages much in the style of the later Country Bear Jamboree.

What caused that project, which was so close to being built, to fall apart was not a dispute over alcohol but what St. Louis was willing to do for and with Disney.

It was the same situation that existed in Florida, but that was resolved when the Florida governor and the state pledged 100 percent cooperation to make the dream a reality. Perhaps they had seen what had happened in St. Louis where Disney easily walked away without looking back.

The Walt Disney Company’s understanding was that they would be responsible for all the costs related to the “show,” meaning the design and building of the rides, creating the films, attention to theming, etc.

They felt that St. Louis would provide the massive building, build parking garages, land improvement (including street traffic) and selling the land itself at a bargain price like in Florida. St. Louis would later be reiumbursed from the net profits of the operation resulting in Disney eventually owning the entire development.

St. Louis was required not to build just the shell but to deliver a facility ready for the installation of the shows and attractions with all the walls and infrastructure. St. Louis felt it should only be responsible for the basic shell with Disney responsible for anything in the interior.

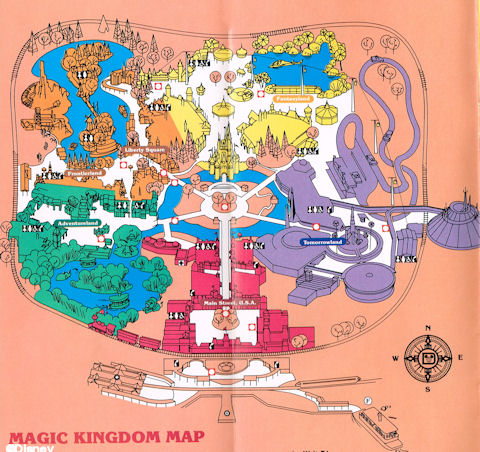

In July 1965, the city and Disney jointly announced that the project would not proceed. In November 1965, Disney officially announced its plans to build an entertainment venue in central Florida, but ideas for some of his previous St. Louis proposals were later incorporated into Walt Disney World.

============

RELATED LINKS

============

Other features from the Walt Disney World Chronicles series by Jim Korkis can be found in the AllEars® Archives.

= = = = = = = = = = = = =

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

= = = = = = = = = = = = =

Disney Historian and regular AllEars® Columnist Jim Korkis has written hundreds of articles about all things Disney for more than three decades.

As a former Walt Disney World cast member, Korkis has used his skills and historical knowledge with Disney Entertainment, Imagineering, Disney Design Group, Yellow Shoes Marketing, Disney Cruise Line, Disney Feature Animation Florida, Disney Institute, WDW Travel Company, Disney Vacation Club and many other departments.

He is the author of several books, including his newest, Secret Stories of Disneyland, available in both paperback and Kindle versions.